Self-Esteem

Self-esteem refers to the judgments and evaluations we make about our self-concept. While self-concept is a broad description of the self, self-esteem is a more specifically an evaluation of the self. Barbara M. Byrne, Measuring Self-Concept across the Life Span: Issues and Instrumentation (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996), 5. If I again prompted you to “Tell me who you are,” and then asked you to evaluate (label as good/bad, positive/negative, desirable/undesirable) each of the things you listed about yourself, I would get clues about your self-esteem. Like self-concept, self-esteem has general and specific elements. Generally, some people are more likely to evaluate themselves positively while others are more likely to evaluate themselves negatively. Joel Brockner, Self-Esteem at Work (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1988), 11. More specifically, our self-esteem varies across our life span and across contexts.

How we judge ourselves affects our communication and our behaviors, but not every negative or positive judgment carries the same weight. The negative evaluation of a trait that isn’t very important for our self-concept will likely not result in a loss of self-esteem. For example, I am not very good at drawing. While I appreciate drawing as an art form, I don’t consider drawing ability to be a very big part of my self-concept. If someone critiqued my drawing ability, my self-esteem wouldn’t take a big hit. I do consider myself a good teacher, however, and I have spent and continue to spend considerable time and effort on improving my knowledge of teaching and my teaching skills. If someone critiqued my teaching knowledge and/or abilities, my self-esteem would definitely be hurt. This doesn’t mean that we can’t be evaluated on something we find important. Even though teaching is very important to my self-concept, I am regularly evaluated on it. Every semester, I am evaluated by my students, and every year, I am evaluated by my dean, department chair, and colleagues. Most of that feedback is in the form of constructive criticism, which can still be difficult to receive, but when taken in the spirit of self-improvement, it is valuable and may even enhance our self-concept and self-esteem. In fact, in professional contexts, people with higher self-esteem are more likely to work harder based on negative feedback, are less negatively affected by work stress, are able to handle workplace conflict better, and are better able to work independently and solve problems. Joel Brockner, Self-Esteem at Work (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1988), 2. Self-esteem isn’t the only factor that contributes to our self-concept; perceptions about our competence also play a role in developing our sense of self.

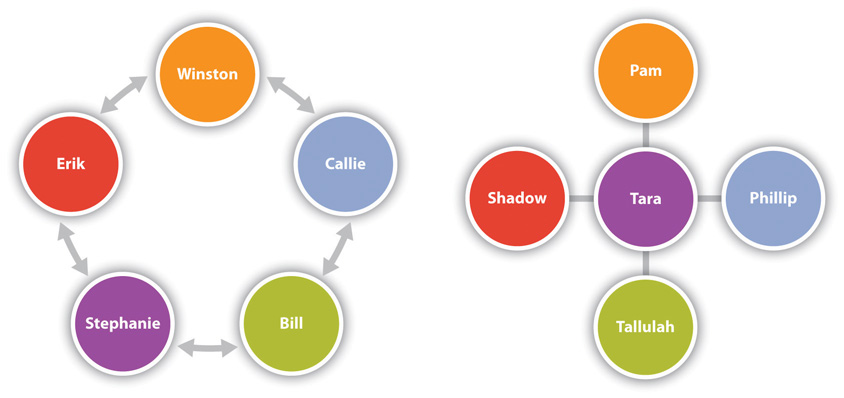

Self-Efficacy refers to the judgments people make about their ability to perform a task within a specific context. Albert Bandura, Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control (New York, NY: W. H. Freeman, 1997). As you can see in Figure 2.2 "Relationship between Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, and Self-Concept", judgments about our self-efficacy influence our self-esteem, which influences our self-concept. The following example also illustrates these interconnections.

Figure 2.2 Relationship between Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, and Self-Concept

Pedro did a good job on his first college speech. During a meeting with his professor, Pedro indicates that he is confident going into the next speech and thinks he will do well. This skill-based assessment is an indication that Pedro has a high level of self-efficacy related to public speaking. If he does well on the speech, the praise from his classmates and professor will reinforce his self-efficacy and lead him to positively evaluate his speaking skills, which will contribute to his self-esteem. By the end of the class, Pedro likely thinks of himself as a good public speaker, which may then become an important part of his self-concept. Throughout these points of connection, it’s important to remember that self-perception affects how we communicate, behave, and perceive other things. Pedro’s increased feeling of self-efficacy may give him more confidence in his delivery, which will likely result in positive feedback that reinforces his self-perception. He may start to perceive his professor more positively since they share an interest in public speaking, and he may begin to notice other people’s speaking skills more during class presentations and public lectures. Over time, he may even start to think about changing his major to communication or pursuing career options that incorporate public speaking, which would further integrate being “a good public speaker” into his self-concept. You can hopefully see that these interconnections can create powerful positive or negative cycles. While some of this process is under our control, much of it is also shaped by the people in our lives.

The verbal and nonverbal feedback we get from people affect our feelings of self-efficacy and our self-esteem. As we saw in Pedro’s example, being given positive feedback can increase our self-efficacy, which may make us more likely to engage in a similar task in the future. Owen Hargie, Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 99. Obviously, negative feedback can lead to decreased self-efficacy and a declining interest in engaging with the activity again. In general, people adjust their expectations about their abilities based on feedback they get from others. Positive feedback tends to make people raise their expectations for themselves and negative feedback does the opposite, which ultimately affects behaviors and creates the cycle. When feedback from others is different from how we view ourselves, additional cycles may develop that impact self-esteem and self-concept.

Self-discrepancy theory states that people have beliefs about and expectations for their actual and potential selves that do not always match up with what they actually experience. Tory Higgins, “Self-Discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect,” Psychological Review 94, no. 3 (1987): 320–21. To understand this theory, we have to understand the different “selves” that make up our self-concept, which are the actual, ideal, and ought selves. The actual self consists of the attributes that you or someone else believes you actually possess. The ideal self consists of the attributes that you or someone else would like you to possess. The ought self consists of the attributes you or someone else believes you should possess.

These different selves can conflict with each other in various combinations. Discrepancies between the actual and ideal/ought selves can be motivating in some ways and prompt people to act for self-improvement. For example, if your ought self should volunteer more for the local animal shelter, then your actual self may be more inclined to do so. Discrepancies between the ideal and ought selves can be especially stressful. For example, many professional women who are also mothers have an ideal view of self that includes professional success and advancement. They may also have an ought self that includes a sense of duty and obligation to be a full-time mother. The actual self may be someone who does OK at both but doesn’t quite live up to the expectations of either. These discrepancies do not just create cognitive unease—they also lead to emotional, behavioral, and communicative changes.

When we compare the actual self to the expectations of ourselves and others, we can see particular patterns of emotional and behavioral effects. When our actual self doesn’t match up with our own ideals of self, we are not obtaining our own desires and hopes, which can lead to feelings of dejection including disappointment, dissatisfaction, and frustration. For example, if your ideal self has no credit card debt and your actual self does, you may be frustrated with your lack of financial discipline and be motivated to stick to your budget and pay off your credit card bills.

When our actual self doesn’t match up with other people’s ideals for us, we may not be obtaining significant others’ desires and hopes, which can lead to feelings of dejection including shame, embarrassment, and concern for losing the affection or approval of others. For example, if a significant other sees you as an “A” student and you get a 2.8 GPA your first year of college, then you may be embarrassed to share your grades with that person.

When our actual self doesn’t match up with what we think other people think we should obtain, we are not living up to the ought self that we think others have constructed for us, which can lead to feelings of agitation, feeling threatened, and fearing potential punishment. For example, if your parents think you should follow in their footsteps and take over the family business, but your actual self wants to go into the military, then you may be unsure of what to do and fear being isolated from the family.

Finally, when our actual self doesn’t match up with what we think we should obtain, we are not meeting what we see as our duties or obligations, which can lead to feelings of agitation including guilt, weakness, and a feeling that we have fallen short of our moral standard. E. Tory Higgins, “Self-Discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect,” Psychological Review 94, no. 3 (1987): 322–23. For example, if your ought self should volunteer more for the local animal shelter, then your actual self may be more inclined to do so due to the guilt of reading about the increasing number of animals being housed at the facility. The following is a review of the four potential discrepancies between selves:

- Actual vs. own ideals. We have an overall feeling that we are not obtaining our desires and hopes, which leads to feelings of disappointment, dissatisfaction, and frustration.

- Actual vs. others’ ideals. We have an overall feeling that we are not obtaining significant others’ desires and hopes for us, which leads to feelings of shame and embarrassment.

- Actual vs. others’ ought. We have an overall feeling that we are not meeting what others see as our duties and obligations, which leads to feelings of agitation including fear of potential punishment.

- Actual vs. own ought. We have an overall feeling that we are not meeting our duties and obligations, which can lead to a feeling that we have fallen short of our own moral standards.